Pleural effusion and ascites

In pleural effusions and ascitesAscites is the abnormal accumulation of serous fluid in the peritoneal (abdominal) cavity. It may be caused by different disorders…, excess fluid that can no longer be removed accumulates inside the body. In a pleural effusionPleural effusion is an abnormal (pathological) collection of serous fluid in the pleural space between the linings of the rib cage and lungs (pleura). It may be caused by different disorders…, the fluid accumulates in the space between the lungs and ribs; in ascites it accumulates inside the peritoneal cavity. Both clinical pictures are consequences of various diseases.

This page provides more information about how pleural effusions and ascites occur, what their causes might be and what treatment alternatives are available.

Please note that this information cannot be used for self-diagnosis and does not replace a physician’s diagnosis.

Pleural effusion

The pleura

The pleura covers the chest cavity from the inside. It covers the ribs from the inside (outer pleura), while also forming the outer protective layer that surrounds the lungs (inner pleura).

The outer pleura and the inner pleura are separated by the pleural cavity, a space that is filled with approximately 5-20 mL of serous fluidSerous fluids are clear, watery fluids that occur in certain cavities of the body. in healthy persons. This fluid acts as a lubricant between the two layers, thus ensuring the mobility of the lungs inside the chest, because the two layers of skin slide against each another during breathing. This mechanism is made possible by the sliding function of the pleura.

Inside the pleural cavity there is negative physiological pressure which holds the lungs in place and allows them to move. This ensures that the lungs can follow the movements of the chest and diaphragm.

Pleural effusion

If the amount of fluid inside the pleural cavity increases, so does the pressure on the lungs, thus decreasing their ability to move. This situation can lead to acute respiratory distress, thoracic pain and dry cough. This is referred to as a pleural effusion.

Depending on the clinical picture, up to 1.5 litres of fluid can accumulate in the pleural cavity. There are two forms of pleural effusions: malignant and benignBenign is the opposite of malignant. Tumours and cancers are classified according to their benign (non-malignant) or malignant cellular changes effusions.

A benign pleural effusion occurs, for example, as a result of left-sided heart failure, liver cirrhosis, fractured ribs or inflammations.

Causes of malignant effusions include tumours in the body, for example cancer, pulmonary embolisms, a bacterial infection with pneumococci within the scope of pneumonia, or rheumatoid arthritis.

What treatment options are available?

The type of treatment that is useful or possible in each individual case always depends on the individual clinical picture and on the patient’s general health. The following treatment alternatives exist:

Pleural puncture

A pleural puncture is an outpatient procedure, which is often performed in the hospital. During the procedure the effusion is punctured with a cannula under local anaesthesia and the accumulated fluid is removed with a syringe.

Chemical pleurodesis

In chemical pleurodesis, the pleural cavity is obliterated under full anaesthesia during an inpatient procedure. To do this, a substance (e.g. powder) is inserted into the pleural cavity that causes the viscera pleural and the parietal pleura to adhere to one another, which in turns prevents fluid from accumulating inside the cavity again.

Permanent drainageIn medicine drainage refers to the systematic withdrawal of increased or diseased fluids, gases and discharges to re-establish normal conditions

In permanent drainage therapy, a catheter is implanted into the pleural cavity in a minimally invasive surgical procedure in the hospital under local anaesthesia. A drainage bottle can be connected to the catheter if the fluid needs to be drained. This is a therapeutic option for recurrent effusions, because it normally allows the patient to return to his usual environment after the implantation and the first drainage. At home, the drainage is performed according to the physician’s instructions.

Ascites

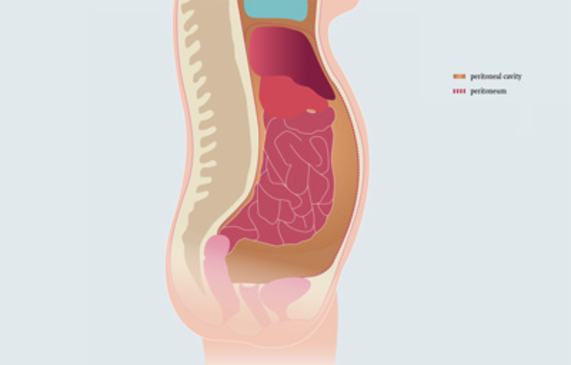

The peritoneum

The peritoneum not only lines the wall of the abdominal cavity, it also encloses most of the organs in the lower abdominal cavity - the liver, spleen, stomach, most of the small and large intestine, and also the ovaries and the fallopian tubes in women.

The thin space separating the two layers is known as the peritoneal cavity. The peritoneal cavity is filled with a small quantity of serous fluid that allows the organs to move inside the abdominal cavity.

Ascites

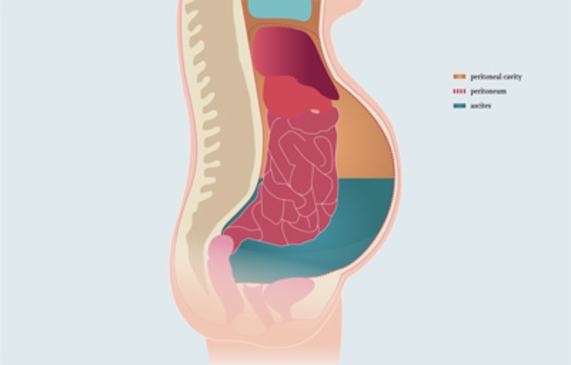

If the quantity of fluid inside the peritoneal cavity exceeds the norm, this is referred to as ascites (abdominal dropsy). This happens if an increased quantity of fluid leaks from the blood vessels into the abdominal cavity (for example, if the pressure in the blood vessels is increased due to organic problems, if pressure is too low due to protein deficiency or increased permeability of the cell walls) and / or if the fluid can no longer be sufficiently removed from the body by the lymphatic system.

Smaller quantities of fluid are usually not noticeable; however, larger quantities cause the abdomen to distend, creating a painful feeling of pressure or a feeling of nausea. Very large quantities of fluid can also obstruct breathing.

There are two types of ascites: benign and malignant ascites.

Benign ascites is generally caused by liver diseases (for example, liver cirrhosis) or heart diseases. Inflammations or injuries of the organs inside the abdominal cavity or acute protein deficiency (hypoalbuminaemia: a decreased concentration of protein in the body means that water can no longer be sufficiently retained in the vascular system and is forced out of the vessels) are also possible causes.

Malignant ascites is caused by tumours. In this context, organ function is frequently impaired to the extent that a greater quantity of fluid is secreted. Alternatively the lymphatic vessels can be affected and are no longer able to remove fluid from the body in sufficient quantities.

What treatment options are there?

The type of treatment that is useful or possible in each individual case always depends on the individual clinical picture and on the patient’s general health.

Abdominal tapping (paracentesis)

Paracentesis is an outpatient procedure. In this procedure, the ascites is punctured with a cannula under local anaesthesia and the accumulated fluid is removed with a syringe.

Electronic pump

In a surgical procedure under full anaesthesia, a small electronic pump is implanted that monitors the quantity of fluid inside the abdominal cavity and – whenever necessary – pumps excess fluid into the bladder via a catheter, from where it is excreted with the urine.

Permanent drainage catheter

The permanent drainage catheter is implanted into the abdominal cavity (peritoneal cavity) in a minimally invasive outpatient or inpatient procedure under local anaesthesia. Whenever necessary a drainage bottle can be connected to the catheter to drain the fluid. After the implantation and the first drainage, the patient is able to return to his usual environment. At home, the drainage is performed according to the physician’s instructions.